Knights of Pythias, Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, Knights of the Maccabees, the Fraternal Order of the Free and Accepted Masons. These American fraternal organizations, many with unfamiliar and almost Medieval sounding names, had memberships in the millions at the beginning of the 20th century, and had a ubiquitous presence in the social life of people across the country. In urban areas, they served as an anchor for neighborhoods, and in small American towns, they operated as community centers for families and business owners, as well as gathering places along Main Street, hosting fish frys, rummage sales and bingo nights. Membership in a fraternal organization was the original social network.

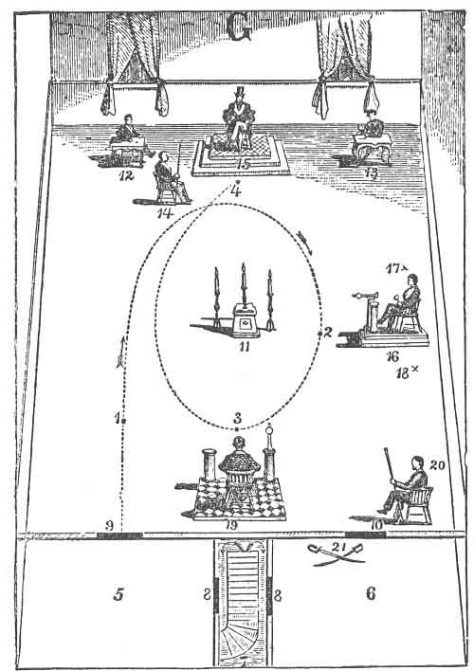

The architecture of American fraternal organizations is one of classicism, mystery and allegory, with an occasional splash of Revivalism that brings a Mughal influence to Milwaukee and the rustic features of a Mayan temple to Aurora, Illinois. The buildings themselves are covered in symbols and emblems, but many are meant to symbols themselves, a testament to the morality, timelessness, and brotherhood that membership in these organizations represented. Their dedication to the intellectual development of members is obvious in their inspiration from high classical architecture, in the same way that houses of worship use the design language and iconography of antiquity to inspire the praise of a higher power. Complex rituals and rites dictated the interior design of these buildings, and many are filled with ante-rooms and chambers for confidential communication. In Masonic lodges, rooms had entrances for different degrees of membership, whether one was an apprentice or Master Mason, with spaces designated specifically for business, ritual or committee.

In communities where vernacular buildings were the norm, fraternal organization buildings were the true stunners. Even some of the simplest temples, housed in common two-story buildings may feature decorative columns flanking the entrance, or a hand-painted annunciator lamp covered in depictions of squares and compasses, five-pointed stars or the letter “G”, representing the role that every act is governed by geometry as well as the “Great Architect of the Universe.”

Many temples, shrines and lodges of fraternal organizations have experienced the same problems that have befallen houses of worship in the mid and late 20th century. With membership declining and stewardship the responsibility of an aging population, large-scale temples, like the South Side Masonic Temple in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood, no longer made sense for the Masons to continue to operate. Constructed in 1921 and designed by Clarence Hatzfield, the South Side Masonic Temple was used as an auditorium and clubhouse through the 1950s until its ownership was transferred to the Department of Human Services. The temple’s second life continued to serve the community until the 1980s, when the Department of Human Services relocated. While redevelopment plans have been presented, the South Side Masonic Temple has slowly deteriorated over its thirty year period of uncertainty, leaving the physical fabric exposed to the elements and leading to numerous building code violations. The South Side Masonic Temple was featured on Landmarks Illinois statewide endangered list in 2015 and Preservation Chicago’s “Chicago 7” most threatened buildings in 2004.

While the current state of the South Side Masonic Temple is a worse case scenario, the Logan Square Masonic Temple in Chicago’s Logan Square neighborhood has fared far better. Constructed in 1923 and also designed by Clarence Hatzfield, the Logan Square Masonic Temple was sold and converted to a house of worship in the 1960s. The Armitage Baptist Church purchased the building in 1982 and has remained there ever since.

Large urban areas have a greater percentage of adaptively reused temples and shrines, while many fraternal organizations in rural areas and small towns are still running out of buildings constructed for their exclusive use. The role that these organizations play within a cultural landscape is largely determined by the size of the population that it serves.

The exclusivity of these organizations has made a sweeping contribution to their decreasing impact. Women are not permitted to join most Masonic lodges, and until the 1970s, the Fraternal Order of Eagles required all members to be Caucasian. While the architectural character of the buildings that fraternal organizations built gives them a reason to be celebrated, their legacy of selectivity and discrimination decreases the emotional significance of these buildings as they were originally intended. A second life as a residential development, event space or house of worship allows them to serve a greater percentage of people in a community, and in many cases makes them not only viable, but neutral.