Read my recent commentary published in the Chicago Tribune below:

Read my recent commentary published in the Chicago Tribune below:

Last year, I had the pleasure of serving as Midwest editor of The Architect’s Newspaper. Here is a selection of pieces I wrote for the publication:

New Wisner-Pilger Public School ties together two small Nebraska towns torn apart by a tornado.

Space p11 brings off-grid art to Chicago’s Pedway.

National Veterans Museum opens in Columbus, Ohio.

What will be Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s legacy on Chicago’s Architecture?

Houston’s Goodnight Charlie’s is a contemporary honky-tonk with vernacular roots.

Chicago needs a new historic resources survey to protect its postmodern and vernacular heritage.

Historic preservation battles in Chicagoland turn to Trumpian tactics.

Perma-Stone, Formstone, faux stone, Rostone. John Waters once called this ubiquitous simulated masonry the “polyester of brick.” From the 1930s through the 1950s, companies all over the United States were pitching faux stone siding to homeowners as a modern update to the exteriors of late 19th century buildings. Made of shale, lime and water, the unbaked permastone slurry would be pressed into stone shaped molds and heated, creating a stone-like “cracker” that could be applied to the exterior of a building. Permastone came in an array of colors, textures and stone types, and sometimes mica would be added for extra sparkle. Widely toted as maintainance free, permastone could be easily adhered anywhere on your building by anchoring it with chicken wire lath, or simply adhering the permastone panels with cement directly to the façade.

The 3400 and 3500 blocks of Le Moyne Street, between Homan and Central Park Avenue in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood, have some superior examples of permastone in nearly every color and texture, from taupe roman bricks to rusticated course stone so red it resembles raw meat. Here is a windshield survey of permastone types seen within these two blocks:

For a few hours each weekday morning, Ronan cracks open the padlock on his forest green wooden newsstand on Division Street between Milwaukee and Ashland, maintaining an urban tradition that has almost completely disappeared. Hailing from a family that made their living off of newsstands, Ronan now operates the newsstand for pleasure, as he makes the argument that “what else is an old blind Polack to do?” Ronan is in fact, blind. He has lost his central vision, but is still able to see people and objects peripherally. This handicap is completely undetectable, as Ronan maintains eye contact as he speaks. His eyes are a shocking neon blue. He’s been operating the newsstand for twenty years, but the newsstand itself has been around for fifty, if not longer. Ronan sells the New York Times, Crain’s, and Barron’s Investment News, but not much else. A rack of Chicago Readers and New York Times Magazines hang off the door of the newsstand, all free items meticulously organized beside a broom and a cart. Every aspect of the newsstand has a reactionary feel. The reflective strips on the door seem to suggest that at some point during the newsstand’s existence, a driver veered too close to the newsstand, knocking the door off. An analog clock, a long ago freebee from USA Today, hangs above an air conditioning unit covered in reflective orange tape. Locks in various conditions suggest multiple lifetimes of securing. Observing the newsstand closed, it resembles a ramshackle stronghold.

The interior of the newsstand is full of Ronan’s personal effects, Beanie Babies, a nest of tangled electrical cords and packages of Rice Crispy Treats. The Rice Crispy Treats are not for Ronan to eat, but to feed the pigeons that come up to window when Ronan is alone in the newsstand. They hold court vigilantly atop the tarred roof when customers approach. There are so few things to buy that the concept of customer seems odd here, as every bus driver, construction worker and Busha seem to know Ronan, but no one is buying anything. They ask how he is. They bring him Makowiec and Perogi. They chat about the weather. These casual relationships at the newsstand are small, but critical. This is why Ronan is here.

It is estimated that the City of Chicago Department of Transportation regulates fewer than 40 independent free standing newsstands like Ronan’s. They have disappeared without advocates, being of a pale vernacular that modern life has hushed, like a lost language.

I’ve drawn all of the places I’ve lived. These drawings, all done informally in ball point pen and within a small Moleskine notebook, were partially inspired by the small-scale architectural models placed in tombs of the Incas, Aztecs and their predicessors in ancient Mexico. Their materials, just like the buildings they portray, are simple. Buried alongside jewelry and ritual objects, these models are vital in their telling of the ordinary, everyday lives of these ancient civilizations.

This exercise also came out of a need for me to see the raw architectural data of each place that I’ve lived, and compare the design, age and typology of each. All of the places I drew I lived for three months or longer. These are the buildings of my ordinary life, all through the filter of my brain and hand.

I have lived in a total mixed bag of buildings, from a contemporary ranch in suburban Detroit, to a modernist highrise in Honolulu, to the ultra vernacular Chicago graystone. These structures range greatly in age. Many are older with a scatterbrained sense of integrity. They have missing cornices, or cheap new windows. Many have design features specific to their location, like the tall concrete wall surrounding the house I lived in when I worked in New Delhi, India, or the attached garage on the house in Troy.

What (and where) we call home inevitably shapes us, but architectural significance has no role in making these structures iconic. I have borrowed time in many buildings but have possessed none of them, and my occupation of each is only a sliver of a story that spans across decades.

The most surprising revelation is poignant and timely. These buildings display an element of undeniable privelidge, as I have always had the means to live where I have wanted. Millions of people are not in a position to ever make that choice for themselves.

On October 13, 2015, Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner held a news conference in Chicago, presenting an aggressive, but perhaps not surprising plan to sell the Helmut Jahn-designed James R. Thompson Center, constructed in 1985. As reported by the Chicago Tribune, it is proposed that the building be sold for cash at a public auction, the over 2,000 state workers moved elsewhere, and demolished, making way for the same-old same-old high-density, mixed use, regrettable architecture.

Rauner had this to say:

“This building is ineffective. For the people who work here, all of whom are eager to move somewhere else, it’s noisy. It’s hard to meet with your colleagues. It’s hard to move through the building, very ineffective, noise from downstairs, smells from the food court all get into the offices”

A lot of people hate this building, but not for its architecture. Taxpayers in Illinois famously hissed over its $172 million dollar price tag, nearly twice its original budget, and a part of history that rings in the ears of people across the state as Springfield continues its own budget deadlock. Helmut Jahn, irresponsible Starchitect and GQ cover subject was so obsessed with the building’s aesthetics that he neglected to develop a way to cool the interior properly, leaving state employees sweating it out for years.

Historic architecture in Chicago’s Loop has been serving the same non-offensive menu year after year, expertly taste-tested by historians, tourists and Chicagoans. Daniel Burnham is clearly the meat course, with Louis Sullivan and his curvilinear forms the vegetables. The starch course is the Rookery, the Railway Exchange Building, and the Reliance Building, with Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe acting as dessert, which many pass on for the swags and acanthus patterns that remain snug and safe along with everything else we have spoiled our appetite with. It’s an outdated bill of fare. It comes as no surprise that the Thompson Center as great architecture was a hard sell as new architecture in 1985, and a hard sell thirty years later as we look forward.

Visit the Thompson Center at noon, and it’s easy to find another reason to hate it. It’s the food smell capital of the Loop. Pizza, Dunkaccinos, Chinese food and Popeye’s all hotboxing inside the steel and glass rotunda. It’s filled with the anxious energy of coworkers in khakis with key cards, camping out at tables downstairs and chewing on the last cubes of ice from their fountain drinks before heading back to their cubicles. Businesses like GNC and the curiously placed Amerinka’s Native Arts & Craft feel as if they are just loitering, and there is certainly a lot of that. People are everywhere, and they are their own system within the building. It’s a frenzy of modern urban life. Chicago is filing for licenses, paying fees, and getting off the train. Then there is the fatal attraction of the building’s spiraling marble floor, a target for nearly a half a dozen jumpers since the building opened thirty years ago.

There is no way to deny the psychological effect of having to go to the DMV, which is another reason the Thompson Center is lauded. Put people in a building where it is expected they will have to wait, experience terrible customer service and inevitably not have the correct form or piece of documentation and it’s impossible to get them to even notice the muted Post-modern color palate as anything more than “puke pink and ugly blue.” It’s like hating U2 because Bono is a pompous ass, and not because every album they’ve put out since 2000 has been crappy.

With a reported $100 million in deferred maintenance, the building has seen better days. The granite panels that served to provide drama to the pedestrian arcade surrounding the building, and as a corral for Jean Dubuffet’s striking Monument with Standing Beast (aka “Snoopy in a Blender”) have been removed. Interior surfaces are rusty, HVAC grates have been kicked in, and there are multiple areas of water damage and spall. But perhaps nothing is as blatantly obvious as the dinginess of the building’s exterior glass panels. It looks dirty from across the street, from above, and from the sky. It’s embarrassing.

This neglect, along with the sub-par tenants and failed driving tests, has given the building a messy reputation, and serves to toxify discussions about the building’s architectural merit. But the new school of cultural heritage preservationists are undaunted, and encouraged by the opportunity to sit on a precipice of sorts, both with the opportunity to preserve postmodern heritage, some of which is just as old as the people in the movement; and aligning that with new ways to talk about how to preserve the architecture of the places that matter. As we move towards a future of cultural resources management where we look at time as more fluid in determining significance, and reject a traditional attitude towards what we consider historic, the sooner we will realize we can serve buildings better, be better stewards and most importantly; serve people by saving beautiful places. And the James R. Thompson Center is a beautiful place.

It’s that magic formula of brains, beauty and fun that makes the Thompson Center a stone cold stunner. Its overstated rotunda is a winking reference to nearly every state capital or county building constructed in the 19th century. Encompassing an entire city block, the primary entrance is set back and tilted towards Chicago City Hall and the Richard J. Daley Center, indicating that the building’s relationship with its surrounding area is a public one.

The colonnade hugging the buildings rounded primary façade is supersized Ancient Rome, and made a conscious decision to ignore all of the architecture afterword until Jahn hit the drawing board in the early 1980s.

Inside, the ceiling soars and the materials are glossy and reflective, while the buildings’ expressed structure focuses and projects.

Light standards are not on the sidewalk outside, but within. And the stairways and escalators have been pulled out from the center core of the building, and placed on the walls of the soaring cavity of the atrium, like fully functioning organs pulled outside of the body. It’s a living organism, a human sized, breathing ant farm. The movement is constant.

The dusty cobalt and creamy tomato soup color palate is America Lite, a political statement that lives comfortably with the Thompson Center as a governmental building. The basic pleasure of the colors and their placement in strong geometric fields appeal to the LEGO builder in you. This is not your father’s Modernism. This is a world where we were imagining the future of buildings, the future of government, and the future of us. On Hoverboards. Even the idealized future is an authentic part of our past, and helps us determine what we build.

Like a song made better as a cover, perhaps the Thompson Center could be improved upon and reimagined using the same care applied to the restoration of other significant; but more mainline, historic Chicago buildings. The cost of repairing the building’s originally failed systems would pale in comparison to the millions of dollars spent to repair Frank Lloyd Wright buildings that were built without downspouts, because Wright didn’t like the way they looked on his vertical line-challenged designs. While each restoration project is unique, Wright’s buildings are a dime a dozen, and Jahn’s is truly one of a kind. Buildings with great stewards like the ones responsible for the brilliant restoration of the Chicago Athletic Association into the Loop’s most creative new/old hangout should be inspiration enough that the nearly impossible is possible (and profitable, too!) Giving the James R. Thompson Center a more creative second life would have a substantial halo effect, both in terms of the preservation of Postmodern buildings, and in Chicago. A significant building worthy of a future we curate and create.

May is National Historic Preservation Month. Preservation organizations at the neighborhood on up to the state level proclaimed “This Place Matters” on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram by holding up a printable sign emblazoned with the phrase and a train of hashtags after it. For many in the field here in Chicago and elsewhere, Preservation Month was business as usual. National Register nominations were drafted, letters to legislators were sent, buildings were researched and photographed, conferences were held and lectures were given. A whole month of work and public reflection that concluded on May 31st, the birthday of Chicago preservationist and photographer Richard Nickel. He would have been 87.

A cake was baked and decorated. Candles were lit. Happy Birthday was sung.

As a student at the Institute of Design in 1954, Richard Nickel was given an assignment in a photography class taught by Aaron Siskind to document works by Chicago School Architect Louis Sullivan. Nickel’s interest in Sullivan’s work metastasized to the point of obsession after the class concluded. Growing up in Logan Square, Nickel was smart but solitary, and had served as a paratrooper and photographer in the US Army but had no defined direction. As Richard J. Daley’s plans for slum clearance surged, demolishing over 6,000 buildings between 1957 and 1960, Richard Nickel was finding purpose in the overlooked work of Sullivan. Documenting and identifying extant buildings designed by Louis Sullivan became Richard Nickel’s life’s work. As wrecking crews approached and a building prepared to meet its fate, Nickel would intervene on behalf of Sullivan’s busy and organic ornament, salvaging what he could and using his parent’s garage in Park Ridge, Illinois to store bits of elaborate stonework and column capitals. Before the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, before the National Trust for Historic Preservation and Preservation Action, before Heartbombs, rightsizing and blexting, Richard Nickel was the only person in Chicago “doing” preservation. He had no language for it. He had no architectural history courses under his belt. He had a Chevrolet, a camera, and a whole lot of fucking soul.

This year, as Chicago’s snow melted and gave way to spring a surge of change began. Demolition permits were filed, and approved. Bulldozers lined up at the ready. Demolition Season has begun, and is surging forward in a way that seems to want to make up for lost time. Good and even great buildings long-mothballed and unoccupied; seemingly waiting for their next chapter since before the financial crisis have been knocked down flat, a blank canvas for new developments with names like “West Town Crossing,” “South Loop Station” or “The Lofts at Roosevelt Village.” Just as often, buildings are demolished without any plan. Coming Soon: Nothing! Chicago’s Landmark Ordinance and demolition delay process is showing its age, seemingly meant for historic architecture with a capital “H” and a capital “A”, and unable to forecast a future where cast iron storefronts had gone from being ubiquitous to rare.

May was also pocked with terror on the regulatory front in Chicagoland, as Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner pushed to dramatically restructure the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, jeopardizing programs such as the admistration of federal historic tax credits and regulatory compliance review. Promoting economic development while preserving the past is a slippery slope, and while the Illinois house approved a measure creating two state agencies for the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum and the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, alleviating some pressure on the issue and allowing the IHPA to remain, it’s still pretty bad news. State Historic Preservation Offices across the country are struggling to maintain functionality under cuts and while this measure is a compromise (the Illinois Legislature will still have to vote) it leaves our SHPO vulnerable, and allows Governor Rauner to appoint a new historic preservation director with senate approval. The state of Illinois’s top job in preservation could be offered up to the gods of cronyism. Bozo the Clown could be the next head of the Illinois SHPO.

Bertrand Goldberg’s Prentice Hospital is now a sodded lot in Streeterville. The vernacular fabric of our neighborhoods are under attack, and the demand for newer, glassier, taller and denser jeopardizes what’s existing. Historic Preservation doesn’t exist in a vacuum, but a lot of practitioners seem to want to keep it in the hands of the gray-haired, bow-tied and time-tested academic, the public sector employee that clocks out of work and out of preservation at 3:30 p.m., or the historian that insists that architectural history stopped after Art Moderne. And we are all still kind of shaking our coffee cans, emblazoned with SAVE THE CLOCK TOWER in front of all those necking teenagers and wondering why no one drops a quarter in. In 2015, there seems to be a breach in connection between historic preservation, determination, appreciation of the works of art that great buildings are and most importantly, inclusion.

It shatters me that we tear down these obvious works of art. I’ll fight the goddamn system till the bitter end, like Dylan Thomas’s poem, “Do Not Go Gently Into The Night”-Richard Nickel

It was not enough for Richard Nickel to take photographs. On June 8th, 1960, Nickel turned from salvager to activist, leading the charge on Randolph Street to save the 1892 Garrick Theatre from demolition. The outcome was a sadly familiar one in the 1960s as well as today, the Garrick was ultimately demolished for a parking garage.

Documenting a building and salvaging its ornament is always a sad sort of consolation prize, but, like Richard Nickel, we cannot let the bitterness over demolition affect our idealism. Like the rebar, wires and other types of building guts revealed as a building is dismantled, letting our determination falter exposes us to the elements and weakens us.

As Richard Nickel understood it, visiting and revisiting Sullivan buildings; watching as they went from being full of life, to becoming unoccupied, documentation was often the last line of defense, and the last chance for a building to ever be known.

Nickel’s work is eyes-straight ahead documentary photography. People are used for scale, and the presence of objects such as light standards and automobiles seem to have been framed so as to purposefully establish time. Architectural photography in Chicago carries the immense weight of this body of work within it. Natural curiousity and thoughtfulness governs each of Richard Nickel’s images. Like piece of double exposed film, almost every photo of an old building takes on a bit of this life.

Great Architecture has only two natural enemies, water and stupid men.- Richard Nickel

Ten years after the loss of the Garrick in a move that seems exponentially stupider then it did at the time, Louis Sullivan’s Chicago Stock Exchange Building was slated for demolition. Advocacy efforts to save the 1894 Stock Exchange proved ineffective, but would ultimately lead to the creation of the Landmarks Preservation Council of Illinois, now Landmarks Illinois. The City of Chicago recognized the importance of the building’s ornament, and paid to have much of it salvaged. The Art Institute of Chicago was to dismantle and recreate the entire Trading Room within one of the museum’s wings. All the while, Richard Nickel photographed the building’s deconstruction, and continued to pull ornament from the site. The Stock Exchange Building was so heavily salvaged and documented that the sum of its exalted existing pieces not so subtly negates the need for it to be demolished in the first place. And for what? Not a parking garage, but the building that replaced it has all the character of one.

When demolition to a building is eminent, it’s popular to state that “Preservationists have lost the battle.” In truth, when a great building is demolished, it’s a battle that we have lost collectively.

On Thursday, April 13th, 1972, Richard Nickel had left home early to salvage inside the Stock Exchange. He was working alone amidst the active demolition around him. It had been unseasonably warm in Chicago that month. Perhaps it was sunny, and the sunshine lit up the dust particles and debris in the air, making it sparkle. That old building smell; damp and warm and made of wood and metal and stone and carpet and everything else, filled the dismantled spaces. Polyester double-knit jacquard shorts were on sale at Carson Pirie Scott & Company, only blocks away. The Stanley Cup-bound Chicago Blackhawks were threatening to strike. US forces were still committed in South Vietnam. Nickel was in love, and recently engaged. It was Richard’s last day on earth.

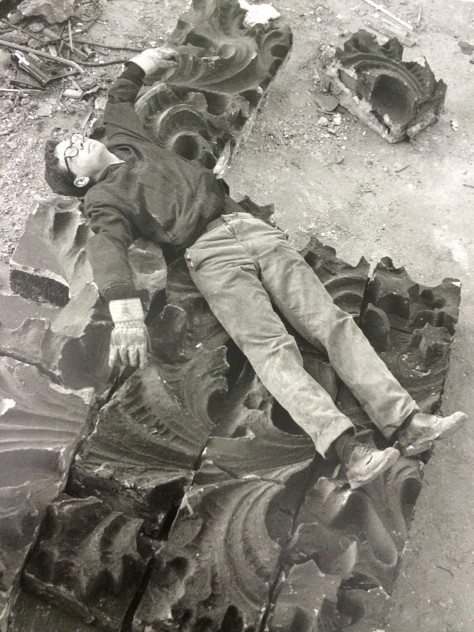

Demolition halted after Richard Nickel didn’t return home, and friends and family searched frantically for him for a week. Almost a month after his briefcase and hardhat were found in the rubble and demolition resumed, a worker spotted what looked like a human shoulder, two floors beneath the Trading Room, in the Stock Exchange’s sub-basement. Richard Nickel had been crushed to death, but his body had remained intact. Debris and rubble, along with cold water seeping into the building had kept decomposition at bay. An autopsy later revealed that Richard Nickel had suffered from pulmonary emphysema and chronic bronchitis, a result of breathing in 20 years of dust and airborne debris from salvage sites and old buildings.

Demolition has a strange way of preserving a building forever, but in time only. The Chicago Stock Exchange never got the opportunity to work through the shift in technology of the 1980s. It never had its mortar joints filled inappropriately, and then lovingly corrected as the culture to physically restore a building continued to mature. It never had the opportunity for its coffee shop to turn into a Currency Exchange, and then to be re-imagined as an Intelligentsia. It will never be listed on the National Register of Historic Places, or be given the opportunity for someone to stealth cellular antennas on the roof.

Richard Nickel is often called a martyr for historic preservation, his death somehow akin to the tragic fate of the source of his obsession, Louis Sullivan. But perhaps canonization throws the bar too far out for us to grasp back onto. Richard was determined and driven by an impetuous passion, remained intellectually curious, and understood the rapid pace of change. These are important characteristics for anyone that practices preservation. Nickel lived for old buildings, and he died for them; but the most important thing to remember is that he really lived, and for something he loved.

At 87, Richard Nickel would have had a wide view of what architectural heritage is today, and it’s doubtful after advocating for the work of Louis Sullivan 50 years after Sullivan’s time it wouldn’t be difficult for Nickel to understand that butterfly roofs are as radical as some of the Chicago School Architecture he was trying to save in the 1960s. He would have championed the shift in ideas of slum clearance and urban renewal to the assets of neighborhoods and Chicago’s vernacular architecture. Perhaps his most recent project would have been documenting the insensitive changes made to C.F. Murphy and Helmut Jahn’s James R. Thompson Center, built in 1985.

Not gently into the night, but loudly expressing his convictions.

Happy Birthday, Richard!

Sandwiched between a rail embankment, Western Avenue and blocks worth of industrial storage in Chicago’s Near West Side are two small streets’ worth of fascinating 1880s Queen Anne workman’s cottages, on the 1300 blocks of South Claremont and South Heath Avenues. Widely attributed to be the work of architect Cicero Hine, and speculated to be an extension of an earlier development on Claremont Avenue , these cottages were added to Landmark’s Illinois Ten Most list of imperiled buildings in 2009 after two blighted cottages came up for the City of Chicago’s fast track demolition program, 1308 South Oakley Avenue and 1302 South Heath Avenue. With no plans for productive reuse and the potential for the cottage’s abandoned status to attract crime and illegal activities, both buildings were demolished in 2010.

With turned Aesthetic Movement decoration at corner eaves and near entryways, plaster ornamentation below rounded windows and playful variations on layout and decoration, these Victorian workman’s cottages are easy to like, and representative of a period where real estate developers worked with notable local architects, like Hine and his contemporary Normand S. Patton to design buildings that stylishly housed the laborers who would go on to build 20th century Chicago.

The two blocks of cottages have an odd secluded quality, a shuttered body shop protects their view from Ogden Avenue, and until ten years ago, the area to the north was comprised of industrial development, now a series of vacant lots with brick and concrete remnants still secured by chain link fences. Freight trains on the rail embankment produce a low, consistent hum. To the northwest is an all-too familiar, but eery site on Chicago’s south and west sides: an empty residential block completely devoid of houses that still retains its layout at ground level, including alleyways and concrete garage pads. In some areas the ground has settled to suggest the foundation of an atypical Chicago two flat.

Every architectural investigation includes observing what’s not there as a key to understanding what is still present, and how to manage the remaining resources. Each of the extant cottages are located on tiny lots, and have little space between them, which makes the presence of the empty lots on South Claremont, South Heath and particularly South Oakley Avenue a stark contrast. Areas of loss here have been extreme, as historic aerial images of the area clearly show, in 1953, this area was three dense blocks of Queen Anne:

Twenty years later, loss was still minimal, and the area remained dense. Between 1971 and 1975, the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency surveyed cottages on Oakley, Heath and Claremont, and as the photographs of individual buildings show, many of them had made it out of midcentury madness retaining an incredible amount of integrity. The original building density and the historic character of the area, nearly a century old, had remained intact. So why not landmark the damn thing? It seems to have had all the right stuff for designation in the early 1970s.

Meanwhile, buildings in Chicago’s loop with National significance were being demolished, an era preservationists wish to forget.

The Near West Side found itself in the early aughts transitioning from an industrial area, into an area serving governmental organizations, the Illinois Medical District and further east, the University of Chicago. Surprisingly, it’s not until after 2000 that dramatic teardowns occurred. By 2002, the loss was substantial. Many of the buildings on South Heath Avenue had been demolished, with four to five lots in a row now devoid of buildings:

In 2013, nearly all of the structures on Oakley Avenue had been leveled, and a boring three-story residential building had popped up in the middle of the block. One late 19th century building has remained, and over time it has developed a door to nowhere.

Perhaps the biggest loss here is that there was a time in history where these two to three blocks were at a confluence between integrity and recognition that was not capitalized upon by giving this area local or national designation. Many of the individual buildings were given an eligibility rating of “Orange” on the Chicago Historic Resources Survey, conducted between 1983 and 1995. This ordinance provides the City of Chicago’s Department of Planning and Development 90 days after the issuance of a building permit to explore preservation options, but in 2014; many of those identified have had their historic character compromised. So is this area eligible for landmark status in 2014? There are definitely better surviving examples of Queen Anne cottages throughout Chicago, with fewer teardowns and more integrity.

While it’s hard to make a convincing case for landmark designation now, the value in these two blocks may have an upswing. It’s a snapshot of what we do with old buildings. For over 130 years in Chicago, people have lived here and continuously changed these cottages to fit their needs. Through changes in the way we live, what we own, how we work and how we relax; these buildings have been altered over time to accommodate modern life. Working class people have been born, lived and died in these buildings. And they have hot rodded the hell out of them!

This area represents such a broad range of material and cladding changes, from wartlike faux midcentury stone on Heath Avenue, gratuitous late 20th century vinyl siding, and literally dozens of different fence types across decades. Perhaps the most interesting facade change is the addition of a balcony on the 2nd floor. Roofs are vinyl shingle, wood shingle and even hot tar. Leaded glass lights have been painted over, covered over, or in some places completely removed.

A few cottages are derelict, 1301 South Heath in particular appears as if the last inhabitants left decades ago.

In terms of integrity, many of these buildings original characteristics are cancelled out by the presence of an obtrusive modern element, leaving only a few with enough original elements to actually render them significant.

It’s difficult to resolve this area’s once outstanding potential for preservation against its current condition, but perhaps there is a place within the study of architectural heritage that also includes the research and observance of vernacular, idiosyncratic changes that preservationists fight so hard to prevent building owners from actually living in the buildings they love, own and live in. Old buildings, new tricks indeed.

At the Presidio, the creator of “Star Wars,” and “Indiana Jones” offered to build and self-endow a $700 million, 95,000 square foot museum to house his nearly $1 billion collection of artwork, ranging from paintings by Norman Rockwell, comics from Mad magazine, and digital stills from the movie Shrek. Lucas has loosely argued that the museum will draw young people to the area that would otherwise not be interested in the park, located just steps away from the Golden Gate Bridge. Lucas also offered this statement about the Bay Area on the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum website:

“The Bay Area has always been home to forward-thinkers and artistic innovators-people who push to do things that haven’t been done before. Men like Eadweard Muybridge, Philo Farnsworth and Steve Jobs. Companies like Pixar, Adobe, and Facebook. There’s a history of invention here that’s as exciting as it is infectious. That’s one of the reasons why I’m here, why I raised my family here, and why I chose to start my own business here. It’s also why I chose this remarkable region for a new museum.”

The Presidio was once the epicenter of military operations in the American West during World War II, but its history began as a military garrison in the 18th century. Many of the 800 some historic buildings, scenic vistas and wooded areas contribute to its’ status as a National Historic Landmark, a unique designation given to only 2,500 historic resources on the National Register of Historic Places. This idyllic location, bordering the shores of both San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean, represents a unique partnership between the National Park Service and the Presidio Trust. The Presidio Trust Act calls for “preservation of the cultural and historic integrity of the Presidio for public use,” and since the park was spared from the auction block in 1996 many buildings have been restored, and brownfields sites cleared to make this a financially independent, desirable mixed use area with ample public space. The Presidio is also the home to Lucasfilm’s Industrial Light and Magic and Lucasfilm’s online offices. So why was Lucas’s plan rejected if he already has a presence there?

The seven member board of the Presidio Trust shot down Lucas’s proposal in February, claiming that it just wasn’t right for the site, an eight-acre parcel known as Chrissy Field, an open space with waterfront access now used as a public recreation area. Similar proposals were also shot down, echoing the commitment of the Trust in terms of the Presidio’s integrity and sensitive development. Lucas isn’t done working on his plan to build a museum in his beloved California. An alternate location has been suggested by the Presidio Trust, and his hometown of Modesto has also expressed interest.

So why does Chicago care about bringing the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum Here? It shouldn’t. But we are coming up with dumb ideas anyways. Let’s discuss two of the worst ideas.

In true Chicago form, no discussion about the significance of the museum is able to happen without establishing a connection between George Lucas, the creative empire that is Lucasfilm, and Chicago. George Lucas’ wife is a native of Chicago. That’s it. There is no other connection. A sketchy Mexican bar in Pilsen didn’t inspire the Mos Eisley Cantina. He didn’t see Ewoks in the trees in Lincoln Park. The campus of Wilber Wright College didn’t inspire the interior design of the Death Star. Sorry.

Some have suggested that Grant Park would make a good location. There are some major problems with this. In 1836, public officials overseeing construction of the Illinois and Michigan Shipping Canal parcelled out the lakefront property that would eventually become Grant Park, legally designating it as “Public Ground — A Common to Remain Forever Open, Clear and Free of any Buildings, or other Obstruction Whatever.” This ordinance is perhaps one of the most well-known in Chicago, and while it has served to protect Chicago’s lakefront in the face of decades’ worth of development challenges there have been some narrow misses, the most recent one being the controversy surrounding the Chicago Children’s Museum’s interest in relocating to Grant Park in 2007. Public outcry created a public relations nightmare for the museum, and the plan was scrapped in favor of a new site on Navy Pier. Grant Park’s proximity to the Loop, the Magnificent Mile and Navy Pier might make this site an attractive but poor option for a museum once again, and any museum with a $700 million dollar budget behind it has ample room to navigate the legal tangles of Grant Park. This is not outside the realm of possibility considering Richard J. Daley was a supporter of the Children’s Museum Plan, and it might already have been suggested by the task force. The price could very easily be right if Lucas was to offer additional philanthropic funds that the City of Chicago could capitalize on.

The Uptown Theater, located in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood, was designed by architects C.W and George Rapp for the Balaban and Katz theatre chain. The Uptown Theatre, built in 1925, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is a notable Chicago Landmark. In what could possibly be one of the most unfortunate stories of long-term preservation by neglect, the Uptown has been dark since the J. Geils Band played a concert there in 1981. No immediate plans for demolition have ever faced the Uptown Theatre, but decades of deferred maintenance and its seemingly constant flux in ownership have kept the building under the radar of organizations like Landmarks Illinois. As recently as January, the Uptown Theatre had its heat turned off, and a 30-foot icicle had formed in the basement. This area of Uptown is a well-known TIF district, and with other smaller scale entertainment venues like the Rivera Theatre and the Green Mill located steps away, bringing the Uptown Theatre back as an entertainment venue similar or congruent to its original use seems like the ideal option. Mayor Emanuel himself even made comments after being elected regarding how he would like to see Uptown as Chicago’s newest entertainment district, but it never happened.

Friends of the Uptown have been lobbying hard via social media to bring the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum to the Uptown Theatre. Perhaps a former theatre housing a collection of artwork that has inspired and contributed to film culture is an alternate take on adaptive re-use, but that argument is a loose one. In Presidio, Lucas proposed a 95,000 square foot museum on what is essentially a raw land sight. How will the Uptown, at a paltry 46,000 square feet ever house that without extensive (and insensitive) renovations? Did we forget what we learned just a decade ago, when we turned Soldier Field into a spaceship? Uptown is a densely developed urban neighborhood, with little room for the infrastructural changes that will affect it once a $700 million, privately funded, nationally recognized museum comes to the area.

And what about parking? This museum will require acres of it, which means that the site chosen will haven an Atom bomb effect in terms of parking in the area. From a preservationist/planner/Urbanist standpoint, this means that buildings that may contribute to the scale or overall sense of place in an area, but aren’t technically or legally architecturally significant might be more financially viable as surface parking lots to their owners. This is a particular concern that should be put in sharp focus for those that believe the Uptown Theatre might make an ideal spot.

Despite already having Lucasfilm as their neighbor, the Presidio made the right choice in turning down Lucas’s plans for a museum in their backyard, and there are even fewer reasons for Chicago to say yes to a large-scale, high-traffic project that doesn’t relate to our existing culture here. The task force in Chicago will report to Mayor Rahm Emanuel in May on their ideal sites for the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum. Perhaps the “force will be with them” and the findings will conclude that the ideal site is somewhere on the planet Tattooine. Or California.

The City of Chicago has created a website where residents can submit ideas and recommend sites for the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum. You can access it here.

Perhaps this is a rhetorical question. In search of an answer, I went to the hospital.

Saints Mary and Elizabeth Medical Center is a doozy of a Brutal building. Located just east of Western Avenue on Division in Chicago, it’s easily the tallest structure in a half-mile radius, and quite out of scale with the rest of Ukrainian Village (and out of context if one considers its famous neighbors, like Louis Sullivan’s iconic Holy Trinity Orthodox Cathedral) With its vertical concrete bastions, tiny punched-out windows and huge hoods looming uneasily, this building is so austere and so brutal it almost makes you want to question the sanity of the architect. Was this person intent on building a structure for health and healing, or was the architect inspired by his laundry hamper turned over an air-conditioning unit?

Brutalism is a design language that came about by rejecting the straightforward glass boxes of Modernist architecture by using materials such as poured concrete and coarse aggregate to express a type of crudeness, or even vulgarity. Brutalism tells it like it is; buildings are a mess of materials and complex systems. Rather than tucking ventilation units in the basement or behind decorative elements, the building becomes a visual expression for the way it actually works. Some of your least favorite buildings are likely in the Brutal style. Take the pugnacious Troy Public Library in Troy, Michigan for example, which looks like it straight up hates itself. Wouldn’t you hate yourself if you looked like a Stair Stepper?

Or a pile of used air filters?

Or the blade of a Ped Egg?

Or a Satanic meat tenderizer throwing up gang signs?

Back to St. Elizabeth, the Brutal exterior gives way to a spectacularly similar interior, where the strong, solid lines and emphasis on material continue.

The Chapel inside was pleasant surprise, with vivid dalle de verre a dramatic contrast to the stark poured concrete, which seems to be the only concession of “pretty” here.

But is my knowledge of architecture clouding my judgment? Brutalism was never meant to compete with the Taj Mahal or your Grandpappy’s favorite old Queen Anne cottage, but it’s certainly distinctive, evenly if it’s distinctively disgusting. These buildings aren’t pretty, but then I couldn’t run speed intervals on the treadmill listening to Peggy Lee. That’s what Skrillex is for.

So the answer is yes, I suppose. I like Brutalism. I like that by serving materials and structure rather than a visually appealing aesthetic, Brutalism developed its own aesthetic that is true to the spirit of really great designs and designers. As Modern architectural heritage begins its journey into the realm of historic significance after years of falling victim to the wrecking ball because it wasn’t pretty or well-liked or Frank Lloyd Wright I can’t help but wonder; will I be the only spinster wacky enough to stand in front of the Chicago Landmarks Commission in 2030 in defense of St. Elizabeth?